UMW

Journal

21

September 1923

Vol.

XXXIV, No. 17

(page

ten)

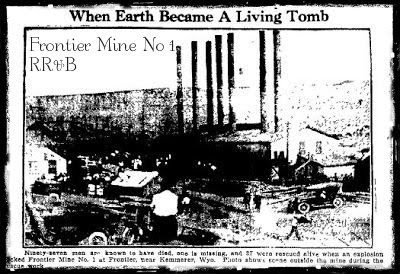

Blast in

Kemmerer, Wyo., Mine Takes Lives of Ninety-Nine Miners

An explosion that snuffed out the lives

of ninety-nine miners and made widows and orphans occurred at Kemmerer, Wyo.,

on august 14, when a terrific blast passed through mine No. 1 of the Kemmerer

Coal Company at Frontier, near Kemmerer.

Thirty-seven men were rescued alive.

The coroner who investigated the

explosion brought in a verdict to the effect that the blast was caused by the

ignition of gas in room seven, thirtieth entry, when the fire boss relighted

his safety lamp.

At the inquest Peter Boam, gas watchman,

produced the lamp he found twelve feet from the face of room number seven,

which was carried by Thomas Roberts, fire boss, whose body was the last found.

State Mine Inspector P.E. Patterson

testified that his inspection of May 17, last, showed the mine was in good condition, with adequate

air.

Immediately upon receipt of news of the

terrible loss of life, the international officials of the United Mine Workers

forwarded a donation of $10,000 to the stricken families of the miners.

The first report of the disaster was

that between 240 and 300 men had met death, and it was several hours until the

shifts of men could be checked up.

T.C. Russell, superintendent of the

Diamond Coal & Coke Company headed the first rescue party following the

explosion. Alex Inanma and Peter Tapero

were among the first survivors to walk out of the mine, coming up the

slope. These men later re-entered the

mine and assisted in the rescue work, although painfully burned.

The body of George Womer, pumpman, was

the first found.

The first to be rescued were three

miners, who were brought out at noon and at midafternoon, twenty-six more were

brought up, the remainder of the 37 rescued were out by 6 p.m., but the work of

bringing the bodies of the victims of the explosion to the surface was not conclude

until Wednesday at 3 p.m., when two more bodies were brought to the

surface.

The last victim to be brought to the

surface was Tom Roberts, whose body was found late Wednesday night. Temporary morgue was established at Odd

Fellows hall in Kemmerer, while bodies were also taken to the Fitzpatrick

morgue while several were taken to the churches for want of room.

Nearly all the fatalities were on the

main slope, the bodies being found head to feet strung along the slope. Comment has been free in Kemmerer as to the

dangerous condition of the mine and the warnings given as to its

condition. The cause of the explosion

will e further investigated. It is but

another example of the conditions that is responsible for the determination of

the United Mine Workers to some such legislation as will make the operation of

coal mines safe for the workers employed therein.

Here is a list of the names of the

victims as furnished by the Kemmerer Republican, whose editor has been tireless

during the fatality:

T. H. Martin, Tom Rankin, George Essman,

John Kiddy, Isaac Roberts, Joe Enright, K. Baba, George Womer, J. A. Walton, S.

Kawase, Matt Metsala, F. Mura, K. Ojima, K. Eojoki, F. Forsman, Nick Smith, K. Kanada, John

Georges, Valandro Faustino, Jos MoTo, Henry Kangas, Joe Wainwright, Sr., Mike

Hill, John Segar, Mike Siterio, Hector Ghiradelli, John Savant, Eno Erickson,

Matt Erickson, V. Coli, Antonio, Ruiz, Joe Rollo, George, Berta, John Segar,

Sr., Louis Timpane, John A. Zumbrannon,

Fred Lodda, Paul Dujine, John Castagna, John Gratiski, Livio Cavechia, Louis

Andrette, Joe Aleo, Tony Brall, Tony Berta, Frank Martinez, Willim Capalli, A.

Beber, Frand Eynon, Pete Palpalmyca, Marton Fontine, S. Masaki, Louis Torisain,

Jno. Christian, Joe Cavach, Marion Pernice, A. Oyass, Joe Rodriguez, Jno. W.

Zumhannan, J. Magino, M. Kosada, George Lupcho, August Jarvie, Oswaldo

Dodorico, T. Nagi, Andrew Impcho, D. Fortunato, Louis Roberts, Robert Toujello,

Jalmar Detsala, C. Nagi, H. Nobara, Mike Kusnerick, Frank Tuabbo, John Peroni,

S. FInamonti, Carl Christianson, John Coli, E. Sever, Joe Lupcho, Max Palaver,

K. Itow, C. Pellegimi, Felix Dodorico, Moroces Magnino, Enio Kare, A. Manapace,

Tom Sanches, Henry Desanti, S. Mikani, A. Aleo, K. Kawalara, Tony Veita, C.

Takasuegi, K. Kirino, C. Mandini, Yalle Valesian, J. Andretta, Paul Warhol, and

Thomas Roberts.

Two Letters

James Morgan, Secretary-Treasurer,

District No. 22, United Mine Workers of America, Cheyenne, Wyoming

Dear

Sir and Brother:

I was deeply grieved to hear of the

dreadful explosion which occurred at the Frontier Mine. The heartfelt sympathy of the entire

membership of our organization goes out to those who are bereft of relatives

and those who have been so terribly injured.

For the purpose of supplying substantial

relief of the victims of this explosion, and their families, I am enclosing

herewith a check for Ten Thousand Dollars.

This is being sent from the International Treasury and I know it will

greatly assist in your work of aiding those who have been the victims of this

great accident.

Please convey to the relatives and

the friends of our organization my deep sympathy in this time of distress.

With every good wish, I am,

Fraternally

yours,

WILLIAM

GREEN

Secretary-Treasurer

Mr.

William Green, International Secretary-Treasurer, U.M.W. of A, Indianapolis,

Indiana.

Dear

Sir and Brother:

I have just returned to the office

from Frontier where the recent mine accident occurred and found your letter and

check for ten thousand dollars awaiting me.

I assure you, Brother Green, that

the prompt response of the national organization was deeply appreciated and a

godsend at this time to both the needy at Frontier and the District

organization.

The death toll was 99 members of the

Local union at Frontier, and the call for aid was more than we would have been

able to meet. We have made arrangements

at Frontier for the relief committee to take care of all matters in connection

with aid required and feel that no child or woman will lace for adequate

attention. It will tide matters over

until the state compensation claims can be adjusted and there will then be

available somewhere around $200,000.00 for the dependents based on what figures

we could obtain at the number of dependents.

It is needless for me to add that

the people most vitally interested, our people at Frontier, will ever remember

the aid rendered to them so promptly, when aid was badly needed.

With kindest personal regards and

best wishes, I remain,

Fraternally yours,

(signed)

JAMES MORGAN

Secretary-Treasurer

District No. 22

Hero of Coal

Mine Explosion Goes Insane from Experiences

Evanston,

Wyo.—John Pavlizon, Austrian coal miner, pronounced the outstanding hero of the

explosion in the Kemmerer Coal Company Mine 1 at Frontier, near Kemmerer, has

been brought to the State Mental Hospital here.

He is insane as a result of his experiences.

At Kemmerer, the day after the mine

disaster, Pavlizon related to an Associated Press correspondent how he had to

fight with his twenty or more companions on 29 level (about one mile under

ground(sic)) to get them to erect

barricades against poison gas.

Blast in

Kemmerer, Wyoming Mine Takes Lives of Ninety-Nine Miners

August 14, 1923

Another Mine

Tragedy

The explosion in Frontier mine near Kemmerer,

Wyo., in which ninety-nine lives were lost gives added emphasis to the campaign

for safety in mines. Through the effort

of one man a score or more of miners were saved, but notwithstanding this, the

tragedy was impressive in in its awfulness.

Those who go down in mines and work for

their daily bread must take what comes—be it good or ill. It is part of the game. The federal government spends much time and

money training miners in safety methods, rescue work and first-aid methods,

some twelve thousand men being trained annually in this respect. But despite this training, accidents will

happen, as the Kemmerer tragedy testifies.

The blame was put on the fire boss of

the Kemmerer Mine for the accident by the coroner, whose verdict was that the

gas in the mine was ignited when the fire boss attempted to relight his safety

lamp. This may or may not have been the

cause—as the fire boss was killed and he is not here to defend himself. It came out in the testimony before the

coroner that complaint had been made previously by the miners of the air

conditions in the workings, but that little attention had been paid to these

complaints by the company. Perhaps there

was negligence here.

It has also developed that the mine

safety laws of Wyoming are inadequate.

This situation probably contributed to the accident. The disaster emphasizes the fact that safety

first in mines depends about as much on the employer as it does on the employe(sic)In other words, there must be laws

and regulations to govern mine safety as well as to teach miners the principles

of rescue and first-aid meets and trained rescuers it would help a lot to have

no accidents.

There is much sympathy expressed for the

families of the killed and injured at Kemmerer.

The international union officials sent $10,000 to the families of the

dead miners. In cases like this the

Union is the friend indeed. Now that the

disaster has come it may be that the state of Wyoming will take steps to

prevent a similar calamity. Or will the

tragedy be shortly forgotten except by those who lost the most?

14 August 2023, received

from Michael R. Dalpiaz, Sr., United Mine Workers of America, International

District 22 Vice President